If you've ever gotten into a debate over healthcare with conservatives, you're very likely to butt heads over a key central issue: Who's going to pay for all this care? I wanted to take a moment to reflect on this question, and in particular consider the idea that these outcomes -- health, life, or death -- are incommensurable. That is, you cannot simply translate these outcomes into a monetary metric. In short, 100 lives does not equal $100.

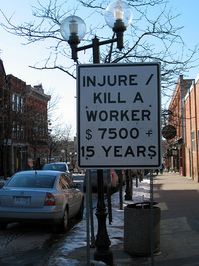

I was recently trying to explain this concept as it relates to healthcare to my students, and I used the following example: "So if I said to each of you, I'm going to die unless you all give me ten dollars, most of you would probably say that this is reasonable and you'd be willing to shell out the dough. But what if that cost goes up to $100? $1000? At some point, you're probably going to say, 'Trevor, I like you very much, but I just can't afford that. Very sorry. Best of luck!'" They all got a laugh out of that, but I think it illustrates the idea that you simply cannot translate one life into some sort of monetary value. This is most strangely illustrated when driving across the country and notice that killing a road worker is valued differently in different states. Here in Michigan, for instance:

Other states have laws that value road workers' lives differently. To say that this is perplexing is a bit of an understatement. Why $7500 and not $10000? When it comes to healthcare, this has been most explicitly debated in regards to things like preventative care. Take for instance the recent debate over mammograms. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force updated its guidelines to suggest that women in their 40s should not have mammograms, because of the risk for false positives: "While roughly 15 percent of women in their 40s detect breast cancer through mammography, many other women experience false positives, anxiety, and unnecessary biopsies as a result of the test, according to data."

Here what we have is a kind of valuation of two outcomes: 15% of women detecting cancer, and a less specific group of "many women" who experience "false positives, anxiety, and unnecessary biopsies" because of the test. This Task Force has made a decision that the latter outcome is too costly to merit the former. Put plainly by the chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society quoted in the article: "With its new recommendations, the [task force] is essentially telling women that mammography at age 40 to 49 saves lives; just not enough of them."

How do you decide what is right and wrong in this scenario? Should all women over 40 get mammograms? Notably, these are just recommendations for care -- there is no mandate behind this guideline that would necessarily prevent a 42 year old woman from receiving a mammogram should she ask. But her doctor may reasonably say that the test is costly (not just financially, but also in terms of medical risks) and statistically her risk of detection is low, and therefore strongly suggest she not get the test. Some doctors may even outright refuse her the test based on the guidelines.

Here we creep up on an even more controversial debate within healthcare: Who controls healthcare decisions -- patients or doctors? With the recent growth of advertising for pharmaceuticals, it's clear that we are moving to a patient-centered approach to healthcare. You diagnose yourself before going to the doctor, and then show up demanding a prescription for Zoloft because you saw a television ad describing symptoms that you then relay to the doctor. We expect doctors to make informed decisions about the various treatments they prescribe, but when faced with a very demanding patient may err on the side of caution.

At the same time, patients with greater access to medical knowledge and resources are much better able to demand the care they think they need -- while patients with lesser degrees of access are unable to do so. Somewhere down the line, you and I are paying for that patient's Zoloft prescription -- whether we like it or not. We're also not paying for countless medications and treatments for patients who either have no access to care or are not as able to demand that care. Thus, there is a socially stratified (by race, class, geography, education, etc) access to treatment based on different levels of access to both services and to knowledge.

I am not enviable with those tasked with legislating these kinds of irrational rationalities (irrational in their incommensurability, rational in their formalized, calculated nature). We not only need to take care to carefully think through how we attach value to health outcomes that are invaluable, but also to consider how these valuations are likely to be socially stratified in their outcomes. Women over 40 might well be good candidates for mammograms, but how many women in the 40s will actually wind up getting that care? And how much are people collectively willing to pay for those mammograms? How much more are we all willing to pay to ensure that any woman who wants that mammogram can get it? $100 a year? $1000? At the end of the day, these are the questions that make healthcare reform downright maddening. There is no right answer. Precisely because there cannot be.

Trevor I must disagree with you. The issue of providing health care to a large population with limited resources is less a moral or ethical one in the first instance and more a logistical problem of providing healthcare to a large population with limited monetary resources. I believe the only reasonable approach one can take in such a scenario is to first attempt to maximize utility: to provide the highest quality of care possible to the most people possible. This includes makes difficult, but ultimately very rational decisions about how to allocate limited resources for providing care. In the case of the example of mammograms. the question of maximizing utility is fairly simple: limited resources should be allocated to those most likely to benefit from them (in terms of very basic outcomes: lifespan, quality of life indices, etc.). Epidemiological research conducted by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force indicates a certain age group of women is less likely to benefit than other groups.

I believe the example you have provided in this instance is a false dilemma. Indeed, I feel as though the argument you have provided has not addressed the real problem of providing healthcare to over 300 million people. The most serious issue here is the refusal of the American populace to understand that the implementing standards of care based on very basic patient outcomes will result in practices that might seem morally abhorrent. A more clear cut example might be withholding extraordinary surgical procedures for the very elderly and infirm. A certain procedure might extend a older persons life by six months, and a younger persons life by many decades. The decision to provide care to one person over the other may appear difficult, but if the concern at hand is providing health care to as many persons as possible (and making best use of those resources based on data), then the correct answer in this case should be obvious.

It is entirely conceivable that in a different society - a gerontocracy for example - old age might be so valued that limited resources for care would be allocated to the elderly. That is not the question currently be debated in Congress, nor as I understand it, in your post. In other countries where medicine has been socialized, many of these "difficult decisions" have already been made to the benefit of the populace - at least everyone gets something. I think that residual religious preoccupations prevent this debate from moving forward. In the meantime, so long as resources are limited as they are our system, so too will healthcare be restricted to those who can afford to the most. Our system for economic reasons is untenable, and we now ought to consider what exactly it is we are trying to accomplish with healthcare reform.

Regards,

Aaron

Aaron, to my understanding you've missed the point. First, you certainly don't know how long that younger person is going to live -- nor do you know how much longer that older person is going to live. Second, the post is arguing that the two are not comparable. Indeed, are six months for one person equally valuable as five years for another? No. That's ridiculous. But in a rationalized framework for healthcare delivery, we're forced to equate them (as you have here). And that's where things become very sticky.

In other words, you act as if "maximizing utility" is always so readily apparent -- and I think that's a bunch of bull.

Trevor,

First, I would like to address your first objection -- that life expectancy is unknown for an older and younger person. On point of fact I disagree, and offer the following life expectancy data in support this:

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus08.pdf#026

Any gerontologist will tell you that the life expectancy of a new born is significantly longer than that of a 75 year old.

Second, I think it is actually quite easy to quantitate the quality of life a lot (but not all) of the time, based on certain quantifiable metrics. An example is the IADL:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/IADL

For example, it would make more sense to treat preferentially those patients who would live longer with better IADL outcomes than those who would live less time and with increased suffering. In such instances, it is likely more patients could be served with a higher overall quality of care. This is a crude generalization, but nonetheless an instructive one.

I also request that you further develop your argument as to the nature of incomprehensibility when addressing quality of life issues.

Regards,

Aaron

Trevor,

I am rereading some of my posts and noticing some egregious spelling and grammar mistakes - please excuse them as I am dyslexic. I will spell check my posts next time.

At any rate, in the last one, I meant incommensurability, not incomprehensibility. My spelling as it happens has rendered my posts incomprehensible.

Aaron